I don’t normally buy animals in bulk. But that was before I decided to dip my toe in the honey-filled pool of beekeeping where you buy bees by the pound and sell honey by the gallon.

That toe-dipping impulse struck as I got to thinking about our wildflower meadows and vegetable gardens. Certainly they’d benefit from a stash of nearby pollinators, yes? As it happened, while I was contemplating keeping bees, I was offered a truckload of beekeeping equipment for free. Boxes, frames, protective gear — the works, all thanks to a beekeeper who decided it wasn’t for him anymore. The universe was sending an unequivocal signal: it’s time for me to stand up an apiary.

After picking up the supplies and being utterly baffled what they were all for, I realized that the only thing I knew about bees and beekeeping is that I didn’t know anything about bees or beekeeping. So, first things first, I signed up for a class with the Beekeepers of the Northern Shenandoah, or BONS.

On a cold January evening, I trudged out to the Virginia State Arboretum for the first of eight weekly classes. I took a seat among 20 or so people who all looked to be auditioning for the part of the store clerk in No Country for Old Men. After a moment, I realized I fit the description, too. Ugh.

“Why are you interested in beekeeping?” the instructor asked. “To pollinate my garden,” several people, including myself, responded. “To help the environment,” said others. “I want honey,” said one or two. “Because I want to be surrounded by tens of thousands of stinging insects,” said nobody.

“To those of you who said you want them to pollinate your garden,” the instructor said, “sure, but you should know that most of the bees will fly right past your garden. They forage over an area of about 30,000 acres. That’s a circle with a four-mile radius. Your garden is a spec.”

Well, then. Still, in for a penny, in for a pound — at $60 a pound, that is.

“The first thing you need to decide,” the instructor said, “is where you plan on putting your hives.” They should be in a sunny spot, facing southeast for morning warmth, off the ground, and in an area with good drainage. “Keep them close to the house,” the instructor advised. “You want them to be convenient so you can visit them often.”

I had never thought about visiting my bees “often,” but as I would come to learn, the key part of beekeeping isn’t the “bee,” it’s the “keeping.”

Meanwhile, the class proceeded to review the different kinds of bees — queens, drones and workers; breeds — Italians, Russians, Carniolan; various bee equipment — bottom screens, supers, feeders, frames and more; all the pests that can kill bees and bedevil beekeepers — fungus, mites, moths, mice, skunks, raccoons, and bears, to name a few; and the annual beekeeping cycle. It was then I realized that keeping bees is less like giving wild animals a home, like with a bird house, and more like keeping livestock — like sheep that need feeding and fencing and shearing and such.

Please Fence Me In

With this information, I considered possible locations and determined that the best spot would be up the hill from the house facing an open area to the southeast. Many hives stand on concrete blocks, but I wanted something a little less construction zone, so I built a raised platform similar to the base of my firewood shelter.

Next, in order to keep my bees from escaping, I bought supplies for an electric fence. Conveniently, I had installed an outdoor outlet nearby, so I was able to use a plug-in energizer to run current through the wires. Also, if you think the fence was to keep the bees in, you need more coffee. It’s actually to keep bears (and other critters) at bay.

Meanwhile, it was time for me to order my bees. Bees can be ordered online and shipped directly to your house, which I’m sure the U.S. Postal Service considers one of their more enjoyable services (though it would seem live scorpions would be a contender for that title). As it happened, though, I was able to order two “packages” from the BONS club, which would include not just three pounds of bees per package, but also a queen, which I would pick up in a few weeks.

While I waited for my bees to arrive, I needed to clean up and prepare their hives. And for that, a trip to the shop was required. Yes!

Boxes of Frames

If you close your eyes and imagine a beehive, you’re likely to envision one of two things: either a conical mass that inspired a generation of terrible hairdos in the 1960s or a stack of multicolored boxes. Those boxes are known as Langstroth hives named after Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, who was a magical bee. No, he was a human and he created the modern standard hive. Inside each box are vertical frames upon which the bees build out honeycomb to raise brood and to store pollen, nectar and, eventually, honey.

The equipment I was gifted included all of the boxes, frames and other pieces necessary for several hives. However, because of various diseases and pests, using old equipment can be risky. I was advised to burn the frames and buy new ones and also to use a blowtorch to scorch the boxes in order to burn off any possible remnants of fungus. Following this guidance meant that I’d need to buy new frames to use for my soon-to-arrive bees.

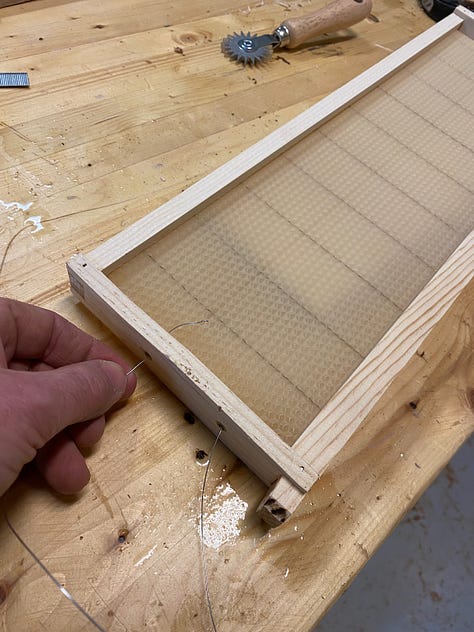

I bought “ready-to-assemble” frames sized for my boxes (boxes come in “shallow,” “medium” and “deep”; mine are “medium”) and followed the instructions to put them together. The assembly process isn’t terribly complex, but neither is it completely obvious.

The frames are made from several pieces of pre-cut pine that need to be glued and nailed together. Inserted through the frame is a piece of what’s called “foundation,” which is either a wax sheet or a piece of plastic. Both have a honeycomb design etched on them that, in theory, the bees use to draw our their comb. I say “in theory,” because I think the bees don’t give two hoots about our etched pattern. They’re going to do whatever they want.

Then, across the foundation you string a thin metal wire to help support the frame for when it’s put into a honey extractor and spun around to fling out the honey.

Since each box holds 10 frames and a beehive could have five boxes and I planned to have two hives (two is considered the minimum suggested), that meant I needed to build 100 frames. Bees aren’t the only ones who stay busy.

Bee Day

I managed to finish charring the used boxes and building the new frames before my bees arrived. Meanwhile, our beekeeping class met at our instructor’s place to get some hands-on (gloves-on) time with bees. We all suited up and headed into his yard, which sported some 20 or so hives and several million bees. This shit was getting real. So, when the day came to pick up the packages I ordered, I was ready.

I drove out to the pick-up point and was handed two boxes of bees, each with about 12,000 buzzing sisters inside, plus a can of sugar water and a caged queen. I plopped them in the trunk of my car and headed home.

The process for “installing” bees is as such, more or less:

Let the bees settle in their package for a day or two, preferably in a cool space like a garage or basement. Spray them with sugar water.

Open the package and pull out the cage with the queen in it. The queen is not related to the other bees; if she was let loose, the other bees would try to kill her. So, they need time to acclimate and accept the queen.

Place the queen cage in the hive and dump 12,000 bees into the hive after her. Pour sugar water in a feeder for them to use. Close up the hive.

After a couple of days, check to see if the queen has gotten out of the cage (there’s a piece of sugar blocking the entrance, which the bees will eat away). If she’s free, remove the cage. If she’s not, uncork the cage and let her out.

Check on the bees a week or two later to see if the queen is laying eggs.

Lucky for me (and the bees), all went according to plan. After a few weeks, eggs were being laid and brood was being raised. Bees were coming and going from the hive, loaded up with pollen. All seemed well.

Watch and Learn

Over the next few months, I mostly just learned to watch the bees. I’d stand near the hive and watch them fly in and out. I’d stand near the “bee bath” (a bird bath filled with rocks and water — bees need water, too!) and watch them take a drink and then zoom back to the hive along some invisible super highway in the sky.

Every so often, I’d open the hives to see what they’d been up to. Pretty quickly they had built comb and started raising their replacements. Although the queen should live for two years or so, the drones and worker bees live for just a 6-8 weeks, usually. That meant that after two months or so, every bee I had brought home and released, save the queen, was likely dead and every bee I saw was instead one of my precious bee babies.

Aside from a few weeks of feeding sugar water, and ensuring that the “bee bath” was well-watered, there wasn’t much for me to do other than watch. The hive started with just one box, but as that filled up with brood, pollen and nectar (probably some from our wildflowers and garden; probably a lot from nearby farm fields), I added a second box, and then a third and then a fourth. Eventually the bees started packing away honey in the top boxes — their food for winter.

Because the bees spent so much of their energy drawing out comb, they haven’t been able to store as much honey is they might otherwise. Therefore it’s unlikely I’ll be able to extract honey this year — I need to leave it for them to survive. But next year, watch out! I expect to have gallons of honey looking for a good home.

One of the reasons it was suggested that I keep two hives was so that I could notice if they started behaving differently from each other — a sign that maybe something was going wrong in one of the hives.

Sure enough, during the height of the summer heat, I noticed thousands of bees congregating at the front of one of the hives. Known as “bearding,” it seemed like they were all practicing an office fire drill. “Everybody out!”

I wasn’t too concerned at first, thinking it was just their way of dealing with the intense, oppressive heat. But because the other hive wasn’t doing the same, I became curious.

I opened each hive and found that the bearding one had three issues:

The frames in the top boxes weren’t being drawn out.

Bees were drawing comb in places where they shouldn’t (like between the bottom board and the bottom frames)

There was a massive ant infestation under the top cover.

I figured all three were related and likely the result of the ants. I suspected I might have spilled sugar water at some point and that drew them to the hive. After consulting with a bee mentor from BONS, I decided to remove the top covers and replace them with fresh covers I had in my stash. That would help eliminate the ant pheromone trails. Then I sealed the cover from the hive and added a Terro ant trap so that the ants, but not the bees, could get to it. One of the challenges in dealing with an ant infestation, I learned was that what kills ants likely will harm the bees as well. So by trying to isolate the ants, I was hopefully able to target just them and spare the bees.

I also added Terro traps to the outside of the hive along the pheromone trails.

As of this writing, I’m still wait to see how well this works. My hope is that the ants will clear out and the bees can resume their routine and catch up to the other hive in terms of honey production. If not, I may have to move frames between the two hives so they can share the food over winter.

In addition to the ants, I also have to test for Varroa mites — the primary killer of colonies these days. These tiny little critters attach themselves to bees and to larvae, ultimately killing them and causing colonies to fail. One way to address the problem is to dribble Oxalic acid over the hives. Once the treatment has had a few weeks to work, you then test its effectiveness by scooping a handful of bees into a jar of rubbing alcohol. After saying a blessing for the bees who about to give their lives for the greater good of the colony, you vigorously shake the jar, which causes the mites to fall off the bees. By counting the mites, you can get a sense of the degree of infestation.

So yeah, the bees are doing the heavy lifting of pollinating crops and making honey, but beekeeping isn’t a lazy man’s hobby either. These little ladies (all workers are female bees) require constant attention.

So how will it all turn out? That remains to be seen. There’s honey, that’s for sure. But will the colonies survive the winter? Will they thrive next spring? We’ll find out.