Tray, Take 2

A few months ago, I built and wrote about a cantilevered tray a colleague of mine asked me to make for his apartment balcony. I was really pleased with how it turned out, but the practicality of it ended up being less than ideal. It was too heavy, my friend said, and because the legs had to be inserted from under the tray, it would be too easy to drop a leg or the entire tray from his 13th-floor balcony to the ground — a mistake that could be quite deadly.

I felt bad that they tray wasn't working for him; I wanted to make sure he had a something that would do the job. We discussed changes to the one I made — hollowing it out to reduce weight; changing how the legs would be inserted — but I didn't love any of the options. Better, I thought, to just make a new one using a different design.

As I mentioned, the main problem with the original tray was that there was no way to install it without either putting the entire tray on the outside of the balcony, or having to install the legs as they dangled perilously above passersby.

As such, what I needed to do was to design the tray so the legs could be "dropped down" from above. This meant putting holes through the entire tray (the original just had recesses underneath). The holes would have an inner that the legs, thanks to their mushroom caps, could hang on to. This would allow the legs to drop down, but not through, the tray. And since I didn't need any bolts coming in through the side, the tray could be thinner and thus lighter.

In the shop, I found several pieces of lumber all of a similar thickness and size. I cut, planed, and jointed the lumber until it was all a uniform thickness. I had a piece of black walnut, two pieces of oak, a piece of what I think is chestnut and another piece that appeared to be hickory.

I glued the planks together and set them aside to work on the legs. Using a thick piece of maple, I cut four sticks, each about 10 inches long and roughly two inches square.

My plan was to keep the first two inches or so of each leg to the full dimension — a so-called mushroom knob — but then slice away about ¼ inch from each side of the legs. The thicker mushroom knob ends is what would keep the legs from falling through the holes.

Meanwhile, I intended to cut small grooves in the mushroom knobs to use as finger grips. And I also wanted to round over the corners of the caps, for comfort.

If I had been thinking, I would have done those things next. But I didn't. Instead, I cut away the excess material from the other eight inches of the legs. And that was a mistake. Why? Because if I worked the knob first, the legs would have sat flush against my work surfaces. But by cutting away the excess material first, I made the sides of the legs unstable and that made the subsequent work harder.

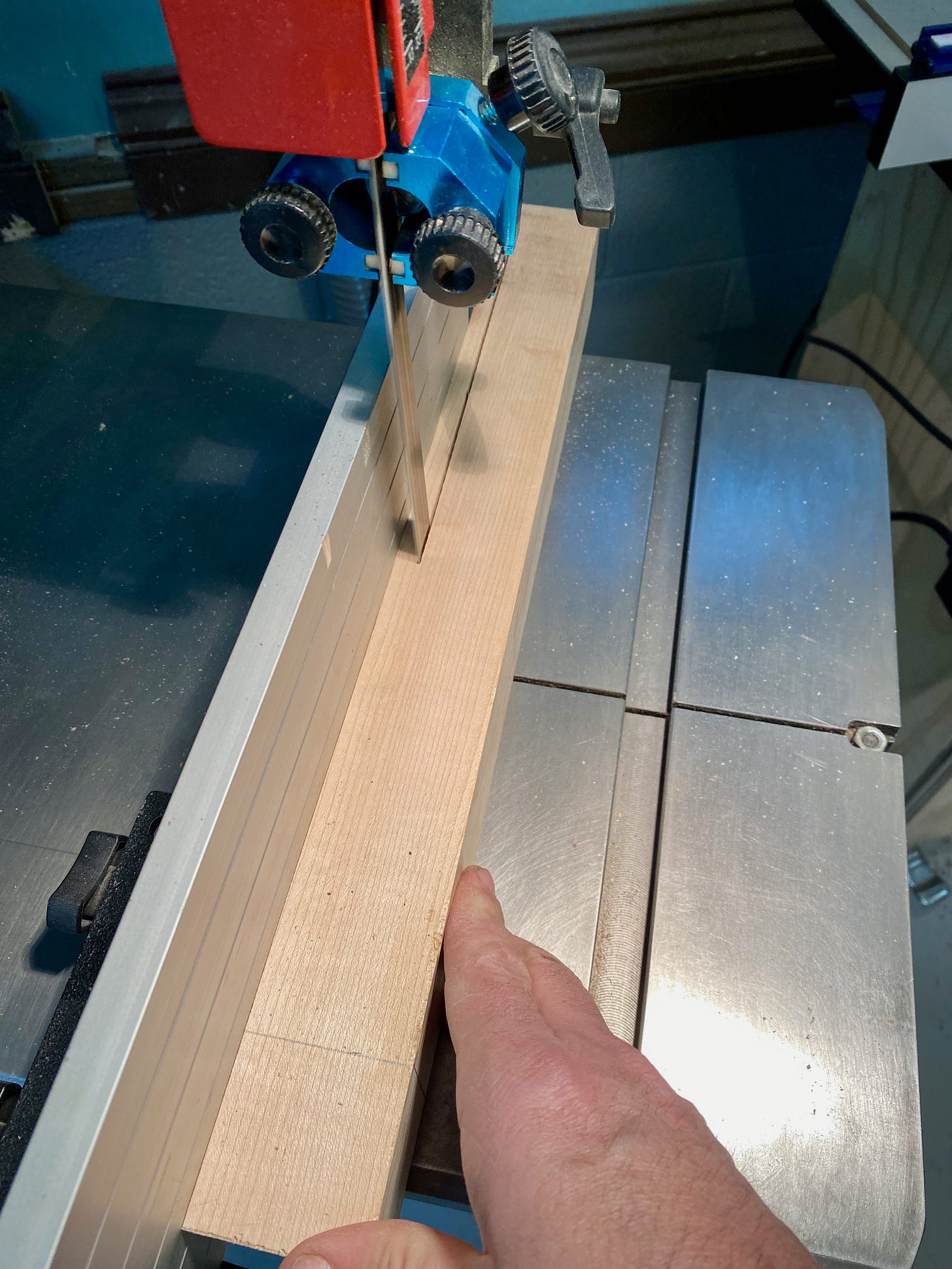

So, proceeding with my out-of-proper-order plan, I took each leg to the bandsaw and carefully cut away the excess material. The cuts weren't perfect, but perfection wasn't my goal (can it ever be?). Instead, I got it pretty, pretty good.

Then I took the legs to the router table and using a chamfer bit, I tried to cut the finger ridges. Besides suddenly realizing my mistake, I struggled to cut the ridges the way I wanted; they were too deep and not straight enough. After a few passes, I decided to change directions and replaced the chamfer bit with a bullnose bit. Instead of making a V-groove in the cap, this bit could make a semi-circle. The cut was cleaned and it was easier — though not easy — to keep the cut straight.

Once I had that set, I used a round-over bit to ease the edges of the legs and the tray itself.

My next challenge was cutting the holes in the tray. At the very least, I needed to cut holes to match the skinny portion of the legs. If I did only that, the legs would drop in and the mushroom caps would sit on top of the tray. For some reason, though, I decided that I wanted to caps to be slightly countersunk into the tray, which meant cutting a shallow ridge around each hole.

Initially I wasn't sure how I would do that, but then I saw an episode of Ask This Old House where Tommy used a rabbeting bit to make just such a ridge. I looked in my router bit tray and lo and behold, I had just such a bit. Brilliant.

The first step in making these holes was to build a jig to use as a template for my router. I cut a few pieces of ½-inch plywood and built the template slightly larger than the dimensions of the legs. Then with the jig securely in place, I used a drill to create an opening through the tray. From there, I used the router to follow the template and cut the perfect hole.

Of course, router bits make round corners and thanks to the shape of the legs, I needed the corners to be pretty square. So I used a jigsaw to cut the inside corners and then a rasp to clean then up.

After cutting the four holes, I tested the fit with the legs — perfect. I even took it to my own brick wall for testing and it worked well, though because the legs had some play in them, the tray sagged. I didn't think this would be a problem for the real application, though, as I had included a pair of wedges with the original tray and thought they could be used to shim this one as needed.

With the initial test complete, I outfitted the router with the rabbeting bit and cut the ridge. Because the rabbeting bit is so large, the inside "corners" of the ridge were also quite large. Again, to make the rectangular legs fit, I needed to cut away the curved corners.

For that, I needed to use a chisel. As I attempted to clean up the inside corners, though, two things happened. First, I was doing a terrible job. The lines weren't smooth and straight. It looked like an earthquake had struck as I was working the wood.

But even worse, the chisel caused the wood to split. Badly. As in, it ruined the piece.

As I looked at the damage, I realized it may have been a blessing. I could just cut away the broken piece, make new holes and instead of trying to square off the inside corners, I'd simply sand the mushroom caps to have round corners themselves.

And that's just what I did. I cut new holes and ridges, left the inside corners of the ridges, and sanded the legs until everything fit.

After a great deal of sanding, I applied an oil-based pre-stain, an oil-based natural stain, several coats of satin laquer and a final coat of paste wax. Once I branded the tray with "Hatchmade," I left it in my friend's office for him to find. (I hadn't told him that a replacement was coming.)

"Wow! Very cool… thanks!," he wrote me when he found it. "I can actually lift it. It will work great."

And in fact, it did work great. The next day he sent me a picture of it in place.