Chicken Run

We're chicken people. Read how that happened.

I guess we became “chicken” people when my wife brought nine chicks home from Tractor Supply in late April. Or maybe it was when I "rescued” a baby quail (I nicknamed it Danny Quail) my dog found in the yard and I then paired with four more chicks so it could be raised in a family.

Could it have been when I spent hours and hours figuring out the best coop to build (or buy)?

It definitely wasn’t when we gave away five of our chickens when they revealed themselves to be roosters and thus had to be separated from each other. But it might have been when we brought a new rooster into the flock and named him Elvis Cluckstello.

In any event, we’re now chicken people with one aforementioned rooster, Elvis, and eight beautiful hens: Martha, Mary Todd, Eleanor, Jackie, Lady Bird, Rosalynn , Hillary and Michelle.

Our descent into becoming chicken people started in late April when Cyn brought home a box of baby chicks. There’s no denying that baby chicks are irrepressibly cute. Barely the size of a mini muffin, they are warm and soft and gentle.

We set the little babies — a selection of Barred Rocks and Rhode Island Reds — up in a nice livestock tub lined with pine shavings and warmed by a pair of heat lamps. Cyn added a Bluetooth temperature gauge so she could monitor their conditions and make sure they were being kept at an appropriate temperature. (For the first week they are to be kept at 95 degrees. Each week thereafter the temperature can drop five degrees.)

We set them up with little feeders and some water and checked on them daily. They grew at a startling rate.

Several weeks later, I discovered our dog playing with something in the lawn. At first I thought it was a frog, but as I got closer I realized it was a baby quail. (Actually, I had no idea what kind of bird it was, but I sent a picture of it to a birder friend and he identified it for me.) I decided the baby quail needed to be rescued (in retrospect, it probably didn’t) and took it to live with the chickens. But it was so much smaller that it seemed dangerous for the quail.

There was only one thing to do: buy more baby chicks so the quail would have some siblings to grow up with. I got four buff Orpingtons and set them and the quail in their own warm and lined container.

Baby chicks are supposed to stay warm and protected for about six to eight weeks. After that, they can go outside and live in a coop.

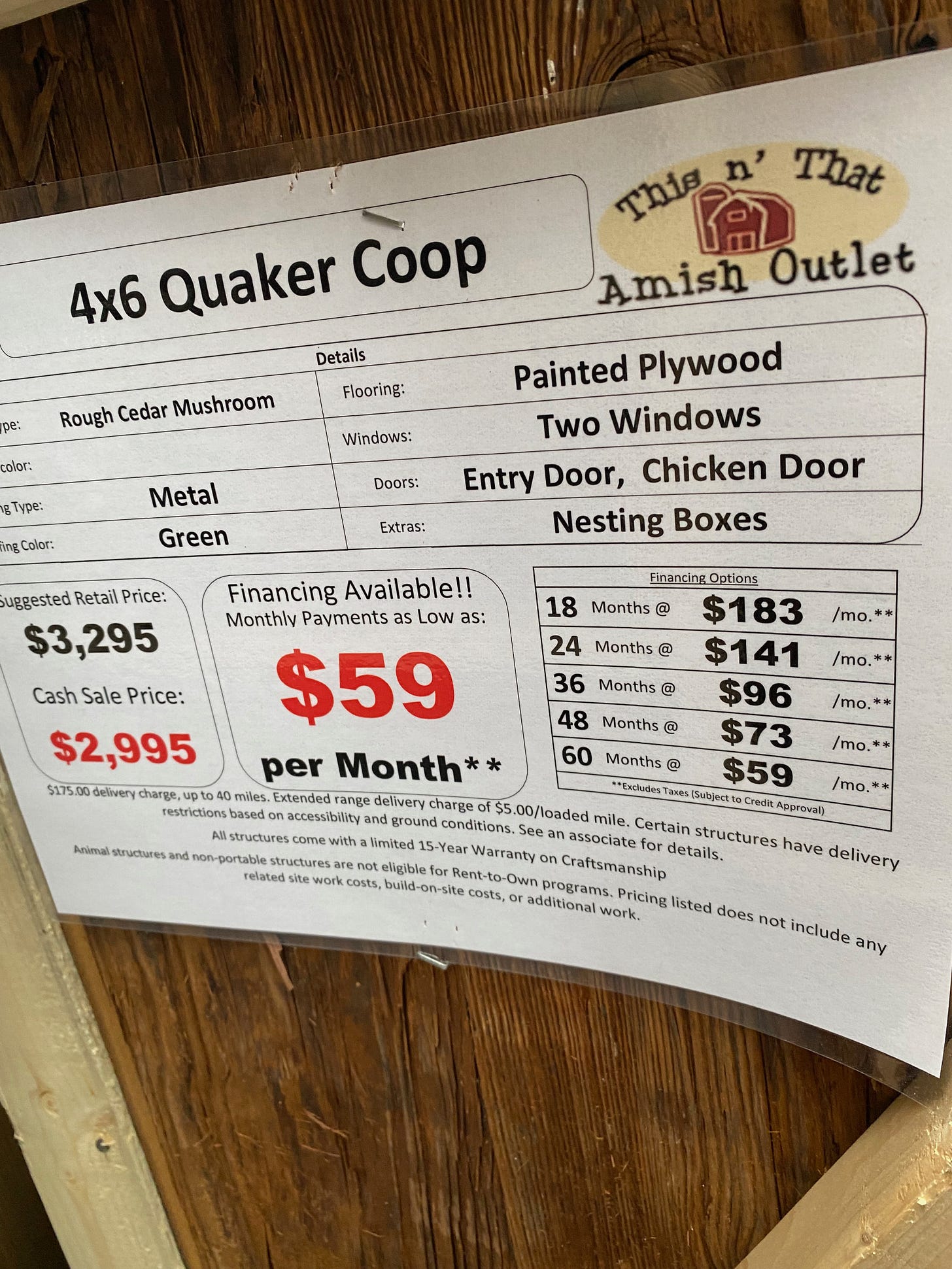

I initially planned to build a coop for our flock and looked at various plans online. I found one I liked that I thought would well for our situation, but when I priced out the materials, I was shocked at the cost. This was partially due to what I hope is a temporary price hike thanks to supply chain/pandemic, but whatever the reason, materials were obscenely expensive.

So I looked around at pre-fab chicken coops. Tractor Supply offers a bunch, but many seemed cheap and destined to fall apart after light use. Others were too small for our flock of 13. Eventually I found a coop that I thought would work well for us at The Chicken Coop Company. I placed my order and waited.

Meanwhile, our first batch of birds were getting big and the second batch — which included the quail — seemed to be getting neurotic. Unlike the first batch, which showed interest in being hand-fed and held, the younger crew was always nervous and seemed discomforted by our attempts to bond. The quail always appeared to be looking for a secret tunnel he could escape through. I began to feel bad for “rescuing him.” Soon he demonstrated some flight skills, so one day I picked him up, took him outside and tossed him into the air. He immediately took flight and took off. Bye bye birdie.

With the quail gone, the Orpingtons quickly settled. They became much less nervous and seemed to enjoy being held and hand-fed. At the same time, the older birds began to undergo some life changes. Five of the nine grew bright red combs and raised tail feathers. We had roosters. Five of them.

Then the coop arrived. Packed in several boxes, it came as a set of pre-assembled panels that had to be screwed together. I watched a YouTube video that showed how it all went together. It was pretty straightforward. I carried the pieces out to the woods and started assembly. Several pieces were difficult to distinguish from each other, but surely it didn’t matter.

In short order, I had the coop and run built, but I realized I had made numerous mistakes — some pieces were in the wrong place or upside down. As a result, certain holes didn’t quite line up, but the whole thing still held together just fine.

Then I concluded that my plan for siting the coop — in the woods behind our house, thinking it would keep odors and noise at bay — wasn’t such a smart location. It was away from where we’d be storing food. There was no electricity, which I wanted for light and maybe heat. Nor was there a source for fresh water. Suddenly it seemed a foolish place to put the coop.

Smarter, I realized, was to assemble it adjacent to our yard barn. That’s where the food would be stored. There’s a water spigot right there. And electricity, too. So, I disassembled the coop, moved it to the new location, and put it back together — the right way this time. As they say, anything worth doing is worth doing twice in order to fix your mistakes from the first time.

With the coop now in its permanent location, I spread mulch around the inside floor and raked gravel around the base to deter digging predators.

Then I ran an extension cable from the yard barn along the run to the coop where I attached an outdoor WiFi outlet into which I plugged an LED rope light. The smart outlet allow me not only to turn the lights on and off remotely, but also to set it to automatically come on before sunset and then off shortly after it gets dark.

I also attached two solar-powered motion-detecting LED lights to (hopefully) scare off any predators — raccoons, foxes, chicken hawks, Kentucky colonels — should they approach at night.

The nearby water spigot, however, proved to be nonfunctional. I turned it on and… nothing. I wasn’t sure how to fix the problem, but then a plumber who was replacing our water pump told me I should blow air into the pipe and see where it comes out. Using my portable air compressor, I did just that and discovered it led to a capped pipe in my basement. I grabbed my plumbing tools and within the hour had reconnected the capped pipe to a cold water source. Now the spigot worked perfectly. Nearby source of water: check.

Lastly, following the manufacturer’s recommendations, I coated the entire coop and run with water sealant to help protect the structure for premature weathering.

At this point, the coop was in move-in condition. We took the older chicks and let them into their new home. They took to it immediately, running up and down the run, ducking inside the coop, and jumping onto the perches.

More changes were coming, though. The roosters were beginning to fight each other, so they had to go. Cynthia found homes for them all — it’s possible some ended up in what a friend of hers calls “freezer camp,” but at least one inherited a harem of hens he could rule over.

With the roosters gone, we began to introduce the Orpingtons. As younger birds, they were immediately relegated to the bottom of the literal pecking order. Several of the older hens seemed to take perverse pleasure in putting them in their place. Martha and Lady Bird seemed to be particularly assertive.

After a few weeks of this bullying, Cyn decided she needed to reset the pecking order. She found on craigslist a rooster that needed a home and upon his triumphant arrival, immediately changed the dynamics in the coop. The Orpingtons were no longer subject to bullying. Everyone started getting along.

Right away, the rooster started singing his cock-a-doodle-doos. With his flashy feathers, macho strut, and vocal range, Elvis was the natural name for him.

As for the hens, experts say birds start laying eggs at about 20 weeks. When we hit that mark, and for two weeks after, we were still eggless. In effort to encourage the First Ladies of Blantyre to be more productive, my wife bought four porcelain eggs to put in the coop. She nestled them in the straw, which I guess somehow would spur the competitive juices of the hens and they'd be like, "woah, we can't let magic eggs beat us at our own game. Let's go, chicken ovaries!"?

In any event, the porcelain eggs were the only ones there until one magical day, Sept. 28, almost exactly 24 weeks since the first hens came home, I opened the box and found a little brown egg sitting the in straw like some sort of present. It was surprisingly exciting, though I'm sure soon enough we'll have more eggs than we can scramble.

Since then, we’ve received about a dozen eggs. As the days grow shorter and colder, egg production tends to wane. So it may be spring before we find ourselves drowning in runny yolks. Until then, we’ll just have to satisfy ourselves with punny yuks.

Sorry.